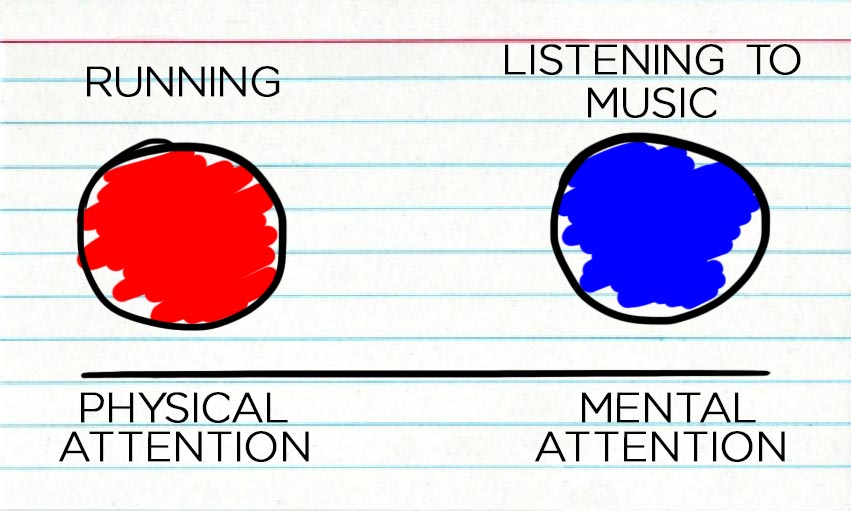

Visualizing "physical" and "mental" attention for multitasking

/While trying to balance dance with our many non-dance career obligations, it's easy to feel like there's not enough time in a day to accomplish everything we intend on. For some people, multitasking is an effective strategy to work on two unrelated tasks at the same time, thus increasing overall productivity. However, not all tasks can be multitasked. The following article should provide you a framework for visualizing which tasks can be completed simultaneously and which cannot.

Multitasking as a time management strategy can help us maximize our daily productivity, but proper multitasking requires an understanding of the human capacity to split our limited attention. Some studies argue that we are only able to focus on a maximum of 2 different tasks at once. As explained on NPR, Vanderbilt neuroscientist Rene Marois believes that each of the hemispheres of the brain handles tasks separately, giving us the capability to complete a maximum of two tasks at once. But by adding a third task, a person may start to lose focus on one or both of the initial tasks.

But, we cannot multitask every pair of tasks. Some tasks can be completed alongside others, while others require complete, undivided attention.

Think of multitasking as a Venn diagram. Each of the two circles represents one of the tasks that you are performing. Running parallel to this Venn diagram is a horizontal spectrum, with tasks on the far left being "physical" tasks, and those on the right being "mental." All tasks fall somewhere along this spectrum.

Understanding "physical" and "mental" attention

On the far left is a red circle that represents tasks that requires 100% of your "physical attention." These kinds of tasks use very little brain power, but requires use of your entire body. For example, running demands every ounce physical attention, since it is literally impossible to do anything else with your body. Even small tasks like checking your phone will cause you to slow down. Tying your shoes would cause you to completely stop running altogether, and this would represent a double-booking of your physical attention.

But, while running, your mental attention is almost completely unused. The repetitive motion of placing one foot in front of the other is a pattern that is intrinsically built into the rhythm of our human body. Because of how natural running can be, the motions are essentially autopilot, requiring very little mental attention (an exception being if you run in Chicago, the City of Potholes, where you'll be playing "Jump the Hole" every few hundred feet.) Because almost no brain power is used during running, your mind is free to wander. Personally, my mind goes to thinking about my next meal, or what funny Facebook status I can post when I share my run time and distance traveled.

Now, refer back to the original Venn diagram. On the right side is a blue circle that represents "mental attention." The simplest example of something that dominates the mental attention is what you are doing right now: reading for comprehension. You will find that reading prevents you from completing other mentally demanding tasks, such as having a conversation or doing advanced calculus. Try finishing this paragraph while simultaneously writing a list of the foods you ate for breakfast and lunch. Although you don't need your hand to read, you'll find that your mental attention is double-booked: although you might be able to complete both these tasks at the same time, you'll miss the main argument of this paragraph while simultaneously misspelling or forgetting items on your list of foods.

Although running takes 100% of your physical attention, while listening to music or reading takes 100% mental attention, the reality is that most tasks use a combination of physical and mental attention. Because of this, every task is represented as a circle instead of a point on the horizontal spectrum.

Consider the task of reading a book. Yes, the bulk of the attention used is mental, as your brain focuses on understanding the text. But, you still need to hold the book, taking up the physical attention of your hands and arms. Your eyes need to focus on the words on the page, preventing your eyes from looking at your surroundings. Even a mentally demanding task such as reading still uses some physical attention.

Using the Venn diagram

To fully take advantage of multitasking as a time management strategy, the two tasks you'll want to perform simultaneously should use different types of attention. In the Venn diagram of your tasks, there should be no overlap in the types of attention used.

Here's a real life example from my work. I spend a lot of my day staring at spreadsheets, despite my red-hot hatred for Excel's God-awful graph making capability. Often times, I find myself copying and pasting until the late afternoon turns into evening. Data analysis uses my entire physical attention, as I click, drag, and Ctrl+V my life away. After sufficient repetition, these physical tasks become a matter of rote muscle memory. This frees up my mental attention to focus on listening to various audiobooks (admittedly, not all educational.)

I encourage you right now to take a few minutes to examine your average workday. Are there moments that require only physical attention, thus freeing up your mental attention to focus on listening to educational podcasts? Short moments in your day such as walking to work are a perfect time to productively listen to music: Make a playlist with songs often used in your preferred dance style and try marking out dance moves in your head. Upcoming performance? Take the seemingly useless minutes while walking to class to mentally perform the choreography in your head.

You may also be related in these articles about multitasking: