Driving while Texting: an example of improper multitasking

/As students / professionals and dancers, we often encounter the age-old problem: not enough hours in a day to accomplish all that we need to. Multitasking, or completing two tasks at the same time, allows us to increase the number of productive hours in a day without sacrificing valuable sleep.

However, multitasking must be done properly. In some cases, our attention is split incorrectly. This could have devastating consequences. An example of how multitasking doesn't always work is described below.

Psychology studies have come to mixed conclusions about the human capacity to multitask. Most studies conclude that our brains are wired to focus on only one or two things at a time. These researchers agree that while we BELIEVE that we increasing our productivity by splitting our focus across two tasks simultaneously, more often than not, we are only doing both things poorly.

We live in a rapidly moving society that values accomplishments, and there is a seeming ever-present pressure to "get stuff done." Study after study insist that multitasking is not a preferred strategy. In fact, a majority of time management articles I have read propose that multitasking is an inefficient waste of time that makes us dumber, rather than a method to accomplish more with your limited time in a day.

But, despite this research, I still remain a strong believer that proper multitasking is an effective time saver. Your success will depend on identifying the RIGHT pair of tasks. They should use a different type of attention - either physical attention or mental attention. You will waste your time when the two types of attention used overlap too much.

An article written by Douglas Merrill gives us some insight into why multitasking won't work for every pair of tasks. The article narrates a vignette from Merrill's life, as he describes a personal experience of how multitasking can go wrong. Trying to text while driving caused the author to rear-end another vehicle on the road. Luckily, no one was injured, but the costly incident caused the author to rethink multitasking. Merrill blames multitasking for the accident, but the truth is that this fender bender was a result of improper multitasking. Merrill had chosen two tasks with overlapping uses of attention, resulting in a double-booking of attention. His attention was split when it should have been focused.

When multitasking fails

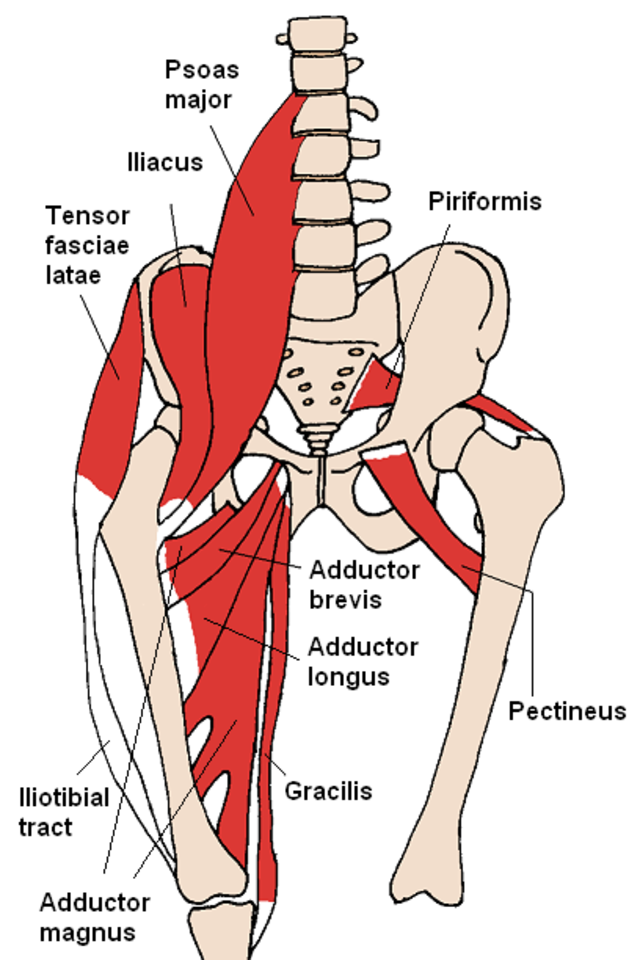

Let's examine how our attention is double-booked when we drive and text by making a Venn diagram (If these Venn diagrams seem like an alien concept, check out this post that explains how we can visualize multitasking.)

As with other Venn diagrams used to understand multitasking, we use colored circles to represent the attention that each of the two tasks requires. Red circles on the left represent physically demanding tasks, while a blue circle on the right represent mentally demanding tasks.

The attention used by driving falls in the middle of the spectrum, with a slight lean to the left: driving requires heavy use of your entire body, from your hands to control the wheel to the feet to control speed. At the same time, driving requires constant awareness of your surroundings, including responding quickly to erratic drivers, being aware of the cars surrounding you, being cognizant of the speed limit relative to your speed, etc. Driving is a predominantly physical task, but requires a great deal of mental attention as well - especially when driving in difficult conditions such as traffic or inclement weather. Compared to running, an almost purely physical task, the red circle in this case no longer falls at the far end of the spectrum, but rather in the middle.

On the other hand, texting falls slightly more on the mental attention side of the spectrum. It requires reading, comprehension of the contents of the message, and thinking of an appropriate response. Texting also requires the use of some of your physical attention: namely, moving your eyes to read the text, moving your hands to hold the phone, and using your fingers to tap out your reply. And so, the blue circle does not belong completely on the right end of the spectrum, but also somewhere in the middle.

The Venn diagram above is the result of what happens when someone opts to do these two tasks at the same time. Both tasks require a fair amount of both types of attention, represented by the red and blue circles overlapping in the middle - hence, the large purple area. This region shows the double-booking of attention that can have negative consequences.

(As a side note, you'll also notice that there are small slivers at the edge of the Venn diagram that are red and blue. These areas represent the capability you have to use 100% focus on one of these tasks. For example, the red crescent on the left is when you are merging lanes on the highway during lunch rush hour - full focus on the road and all the hangry drivers surrounding you. The blue crescent is when you get stuck at the red light in front of your destination restaurant, where you sneak the time to fire off a quick "be there soon" text to your waiting lunch partner.)

When you multitask your way through your day, think about the pair of tasks you have chosen. If you are driving and listening to an educational lecture, can you recall the major concepts of the lecture when you arrive at your destination? If not, most likely you are spending your mental attention on driving. You are better off learning at a time where you can spend all your mental attention on the lesson.

These articles related to multitasking may also be interesting to you: